One of the things that really sucks about doing online code reviews is that, in all the systems I know, your code reviews do not integrate with your source control. If the code reviews are versioned at all—and they’re frequently not—then they’re in an entirely different system than your real VCS. For larger reviews, where you’re talking about a major piece of functionality, that means that your source control system will end up lacking the history of how a feature came to be. In other words, the more you use code reviews, the less actual history you have in your VCS.

That’s totally broken. You’re being punished for doing the right thing.

A little over a year a year ago, Tyler came to me and asked me to join him in the Django Dash, a weekend code sprint. Tyler and I had been talking about the code review problem, and had been thinking of writing our own that lacked these issues. Django Dash seemed like the perfect time to try to actually do that.

That opened up a question: how do you actually achieve better code review? If you accept that a huge part of the problem is that the code review history is out-of-stream with your VCS, then it follows that you have to somehow store the in-process code in the VCS.

In most systems, that means using branches. But branches in almost any system suck. Everyone has a horror story about trying to do a merge in Subversion, or CVS, or Perforce—and these are usually not meaningfully large merges; just small feature branches. Trying to use branches for long-running code reviews in these systems simply isn’t viable.

But DVCSes are great at handling this kind of problem. To be distributed, they have to have extremely robust branching and merging systems. Because their systems are so good, it’s very common in DVCSes to do quick experiments and features in their own branch, then merge when complete.

Tyler and I were both big fans of Mercurial (in fact, we convinced all of Fog Creek to switch to Mercurial from Subversion), so using Mercurial as our DVCS base seemed like the best bet. After some discussion of the technical details for making the system work, we got a good night’s sleep, woke up early, threw a nice breakfast on the table, and started coding.

Forty-eight hours later, we had our first prototype. When users wanted to contribute code to a repository, they would fork the repository, push all of their changes to the fork, and then request a review on the fork. Users would see the exact diff of what they would be approving to the repository; no more, no less. Code could not be approved unless it had already merged in the trunk, ensuring that the user who wrote the code had taken care of the merge. When the review was approved, it’d be seamlessly merged into trunk (guaranteed seamlessly, due to the previous rule), with full history.

The design was inflexible and unintuitive, and would have had serious issues in a shipping project, but we achieved what we set out to do:

- Approving a code review was the same as pushing it

- Which meant that we could fully separate the concepts of code author and code approver

- And which meant that the full history of reviewed code was completely preserved

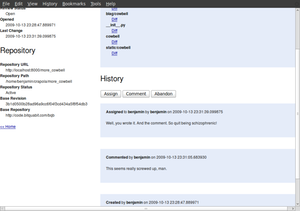

A screenshot of the prototype that would later become Kiln

Even in its nascent form, the tool was already impressive enough, and unique enough, that we won the Django Code Dash.

Tyler and I talked of making our code review tool into a real product, but we were knee-deep in Copilot work, so it had to wait. But we had proved, if only to ourselves, that using a DVCS, even in a centralized model, provided some very unique capabilities that simply were not possible in other systems.

When Joel announced a few months later that FogBugz needed a source control system, we’d be ready.

Want to comment on this post? Join the discussion! Email my public inbox.